On October 19, 2011, FDA released a document1 which provides an overview of factors that potentially contributed to the contamination of fresh, whole cantaloupe with the pathogen Listeria monocytogenes which was implicated in a multi-state outbreak of listeriosis. In early September 2011, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), in conjunction with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and state health departments, began to investigate a multi-state outbreak of listeriosis. Early in the investigation, cantaloupes from Jensen Farms in the southeast region of Colorado were implicated in the outbreak.

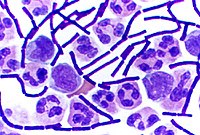

On September 10, 2011, FDA, along with Colorado state officials, conducted an inspection at Jensen Farms and collected multiple samples, including whole cantaloupes and environmental (non-product) samples from within the facility, for laboratory analysis to identify the presence of Listeria monocytogenes. Of the 39 environmental swabs collected from within the facility, 13 were confirmed positive for Listeria monocytogenes with pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) pattern combinations that were indistinguishable from three of the four outbreak strains collected from affected patients. Of the 13 positive environmental swabs, 12 were collected at the processing line and 1 was collected from the packing area. Cantaloupe collected from the firm’s cold storage during the inspection was also confirmed positive for Listeria monocytogenes with PFGE pattern combinations that were indistinguishable from two of the four outbreak strains.

FDA Environmental Swabs Positive Results

Processing Line

9 positive samples from the grading belt

Swabs 21, 22, 23, 24, 26, 27, 29, 30 & 33

2 positive samples from the conveyor

Swabs 20 & 28

1 positive sample from the felt rollers

Swab 13

Packing Area

1 positive sample from the conveyor belt

Swab 34

FDA Product Sample Results

1 Cantaloupe Sample collected from cold storage

5 subs tested positive

(10 whole cantaloupes or “Subs”)

Please refer to the section below for

FDA’s Sample Records and Results on Jensen Farms

As a result of the isolation of outbreak strains of Listeria monocytogenes in the environment of the packing facility and whole cantaloupes collected from cold storage, and the fact that this is the first documented listeriosis outbreak associated with fresh, whole cantaloupe in the United States, FDA initiated an environmental assessment in conjunction with Colorado state and local officials. FDA, state, and local officials conducted the environmental assessment at Jensen Farms on September 22-23, 2011. The environmental assessment was conducted to gather more information to assist FDA in identifying the factors that potentially contributed to the introduction, growth, or spread of the Listeria monocytogenes strains that contaminated the cantaloupe.

FDA identified the following factors as those that most likely contributed to the introduction, spread, and growth of Listeria monocytogenes in the cantaloupes:

Introduction:

There could have been low level sporadic Listeria monocytogenes in the field where the cantaloupe were grown, which could have been introduced into the packing facility.

A truck used to haul culled cantaloupe to a cattle operation was parked adjacent to the packing facility and could have introduced contamination into the facility.

Spread:

The packing facility’s design allowed water to pool on the floor near equipment and employee walkways.

The packing facility floor was constructed in a manner that made it difficult to clean the packing equipment was not easily cleaned and sanitized; washing and drying equipment used for cantaloupe packing was previously used for postharvest handling of another raw agricultural commodity

Growth:

There was no pre-cooling step to remove field heat from the cantaloupes before cold storage. As the cantaloupes cooled there may have been condensation that promoted the growth of Listeria monocytogenes

FDA’s findings regarding this particular outbreak highlight the importance for firms to employ good agricultural and management practices in their packing facilities as well as in growing fields. FDA recommends that firms employ good agricultural and management practices recommended for the growing, harvesting, washing, sorting, packing, storage and transporting of fruits and vegetables sold to consumers in an unprocessed or minimally processed raw form.

FDA has issued a warning letter2 to Jensen Farms based on environmental and cantaloupe samples collected during the inspection. FDA’s investigation at Jensen Farms is still considered an open investigation.

On September 10, 2011, FDA, along with Colorado state officials, conducted an inspection at Jensen Farms and collected multiple samples, including whole cantaloupes and environmental (non-product) samples from within the facility, for laboratory analysis to identify the presence of Listeria monocytogenes. Of the 39 environmental swabs collected from within the facility, 13 were confirmed positive for Listeria monocytogenes with pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) pattern combinations that were indistinguishable from three of the four outbreak strains collected from affected patients. Of the 13 positive environmental swabs, 12 were collected at the processing line and 1 was collected from the packing area. Cantaloupe collected from the firm’s cold storage during the inspection was also confirmed positive for Listeria monocytogenes with PFGE pattern combinations that were indistinguishable from two of the four outbreak strains.

FDA Environmental Swabs Positive Results

Processing Line

9 positive samples from the grading belt

Swabs 21, 22, 23, 24, 26, 27, 29, 30 & 33

2 positive samples from the conveyor

Swabs 20 & 28

1 positive sample from the felt rollers

Swab 13

Packing Area

1 positive sample from the conveyor belt

Swab 34

FDA Product Sample Results

1 Cantaloupe Sample collected from cold storage

5 subs tested positive

(10 whole cantaloupes or “Subs”)

Please refer to the section below for

FDA’s Sample Records and Results on Jensen Farms

As a result of the isolation of outbreak strains of Listeria monocytogenes in the environment of the packing facility and whole cantaloupes collected from cold storage, and the fact that this is the first documented listeriosis outbreak associated with fresh, whole cantaloupe in the United States, FDA initiated an environmental assessment in conjunction with Colorado state and local officials. FDA, state, and local officials conducted the environmental assessment at Jensen Farms on September 22-23, 2011. The environmental assessment was conducted to gather more information to assist FDA in identifying the factors that potentially contributed to the introduction, growth, or spread of the Listeria monocytogenes strains that contaminated the cantaloupe.

FDA identified the following factors as those that most likely contributed to the introduction, spread, and growth of Listeria monocytogenes in the cantaloupes:

Introduction:

There could have been low level sporadic Listeria monocytogenes in the field where the cantaloupe were grown, which could have been introduced into the packing facility.

A truck used to haul culled cantaloupe to a cattle operation was parked adjacent to the packing facility and could have introduced contamination into the facility.

Spread:

The packing facility’s design allowed water to pool on the floor near equipment and employee walkways.

The packing facility floor was constructed in a manner that made it difficult to clean the packing equipment was not easily cleaned and sanitized; washing and drying equipment used for cantaloupe packing was previously used for postharvest handling of another raw agricultural commodity

Growth:

There was no pre-cooling step to remove field heat from the cantaloupes before cold storage. As the cantaloupes cooled there may have been condensation that promoted the growth of Listeria monocytogenes

FDA’s findings regarding this particular outbreak highlight the importance for firms to employ good agricultural and management practices in their packing facilities as well as in growing fields. FDA recommends that firms employ good agricultural and management practices recommended for the growing, harvesting, washing, sorting, packing, storage and transporting of fruits and vegetables sold to consumers in an unprocessed or minimally processed raw form.

FDA has issued a warning letter2 to Jensen Farms based on environmental and cantaloupe samples collected during the inspection. FDA’s investigation at Jensen Farms is still considered an open investigation.