The Mughal era is a historic period of the Mughal Empire in South Asia (mainly Northern India, North Eastern Pakistan and Bangladesh). It ran from the early 15th century to a point in the early 18th century when the Mughal Emperors' power had dwindled. It ended in several generations of conflicts between rival warlords.

The imperial family directly descended from two of the worlds greatest conquerors: Genghis Khan, founder of the largest contiguous empire in the history of the world; and the Amir, Taimurlong or Tamerlane the Great. The direct ancestors of the Mughal emperors, at one point or another, directly ruled all areas from Eastern Europe to the Sea of Japan, and from the Middle East to Russian Plains. They also ruled some of the most powerful states of the medieval world such as Turkey, Persia, India and China. Their ancestors were further also credited with stabilizing the social, cultural and economic aspects of life between, Europe and Asia and opening the extensive trade route known as the Silk Road that connected various parts of the continent. Due to descent from Genghis Khan, the family was called Mughal, or mogul, persianized version of the former's clan name Mongol.The English word mogul (e.g. media mogul, business mogul) was coined by this dynasty, meaning influential or powerful, or a tycoon. From their descent from Tamerlane, also called the Amir, the family used the title of Mirza, shortened Amirzade, literally meaning 'born of the Amir'.[2] The burial places of the Emperors illustrate their expanding empire, as the first Emperor Babur, born in Uzbekistan is buried in Afghanistan, his sons and grandsons, namely Akbar the Great and Jahangir in India and Pakistan respectively and later descendants, Shah Jahan and Aurangzeb in Hindustan. The last Emperor, Bahadur Shah Zafar is buried in Burma.

They were also a prominent influence of literature in Urdu, Hindi, and Bengali. They have been continuously portrayed in many films, the most famous of which, multi-million dollar Mughal-e-Azam about Emperor Jahangir's love story; considered an Indian classic and epic film and also the Bollywood film Jodhaa Akbar about Emperor Akbar's (Emperor Jahangir's father) love story. Emperor Jahangir's son was the Prince Khurram who later went on to become Emperor Shah Jahan and built one of the seven Wonders of the World, the famous Taj Mahal to memorialize his love for his wife.

The titles of the first of the six Mughal Emperors receive varying degrees of prominence in present-day Pakistan and India. Some favour Babur the pioneer and others his great-grandson, Shah Jahan (r. 1628-58), builder of the Taj Mahal and other magnificent buildings. The other two prominent rulers were Akbar (r. 1556-1605) and Aurangzeb (r. 1658-1707). Both rulers expanded the empire greatly and were able administrators. However, Akbar was known for his religious tolerance and administrative genius, whereas Aurangzeb was a just ruler but a proselytizer of orthodox Islam across the heterodox Indian landscape.

Babur kept the record of his life in Chagatay Turkish, the spoken language of the Timurids and the whole Turco-Mongol world at the time. Baburnama is one of the longest examples of sustained narrative prose in Chagatai Turkish. Akbar's regent, Bairam Khan, a Turcoman of eastern Anatolian and Azerbaijani origin whose father and grandfather had joined Babur's service. Bayram Khan wrote poetry in Chaghatai and Persian. His son, Abdul-Rahim Khankhanan, was fluent in Chaghatai, Hindi, and Persian and composed in all three languages. Using Babur's own text he translated the Baburnama into Persian. The Chaghatai original was last seen in the imperial library sometime between 1628 and 1638 during Jahangir's reign.

In 1539, Humayun and Sher Khan met in battle in Chausa, between Varanasi and Patna. Humayun barely escaped with his own life and in the next year, in 1540, his army of 40,000 lost to the Afghan army of 15,000 of Sher Khan. A popular Pashtun Afghan General "Khulas Khan Marwat" was leading Sher Shah Suri's Army. This was the first Military Adventure of Khulas Khan Marwat and he became soon, a nightmare for Mughals.

Sher Khan's Army under the command of Khulas Khan Marwat had now become the monarch in Delhi under the name Sher Shah Suri and ruled from 1540 to 1545. Sher Shah Suri consolidated his kingdom from Punjab to Bengal (the first to enter Bengal after Ala-ud-din Khilji, more than two centuries earlier). He was credited with having organized and administered the government and military in such a way that future Mughal kings used it as their own models. He also added to the fort in Delhi (supposed site of Indraprastha), first started by Humayun, and now called the Purana Qila (Old Fort). The Masjid Qila-i-Kuhna inside the fort is a masterpiece of the period, though only parts of it have survived.

The charred remains of Sher Shah were taken to a tomb at Sasaram (in present day Bihar), midway between Varanasi and Gaya. Although rarely visited, the future great Mughal builders like Akbar, Jahangir and Shah Jahan emulated the architecture of this tomb. The massive palace-like mausoleum is three stories and fifty meters high., Sher Shah’s son Islam Shah held on to power until 1553 and following his death the Sur dynasty lost most of its clout due to strife and famine.

Humayun was a keen astronomer, and in fact he died due to a fall from the rooftop of Sher Shah’s Delhi palace in 1556. Thus Humayun ruled in India barely for ten years and died at the age of forty-eight, leaving behind Akbar then only thirteen-year-old as his heir. As a tribute to his father, Akbar later built the Humayun’s tomb in Delhi (completed in 1571), from red sandstone, that would become the precursor of future Mughal architecture. Akbar’s mother and Humayun’s wife Hamida Banu Begum personally supervised the building of the tomb in his birth place.

Akbar's methods of administration reinforced his power against two possible sources of challenge—the Afghan-Turkish aristocracy and the traditional interpreters of Islamic law, the ulama. He created a ranked imperial service based on ability rather than birth, whose members were obliged to serve wherever required. They were remunerated with cash rather than land and were kept away from their inherited estates, thus centralizing the imperial power base and assuring its supremacy. The military and political functions of the imperial service were separate from those of revenue collection, which was supervised by the imperial treasury. This system of administration, known as the mansabdari, was based on loyal service and cash payments and was the backbone of the Mughal Empire; its effectiveness depended on personal loyalty to the emperor and his ability and willingness to choose, remunerate, and supervise.

Akbar declared himself the final arbiter in all disputes of law derived from the Qur'an and the sharia. He backed his religious authority primarily with his authority in the state. In 1580 he also initiated a syncretic court religion called the Din-i-Ilahi (Divine Faith). In theory, the new faith was compatible with any other, provided that the devotee was loyal to the emperor. In practice, however, its ritual and content profoundly offended orthodox Muslims. The ulema found their influence undermined.

Several well known heritage sites were built during the reign of Akbar. The fort city of Fatehpur Sikri was used as the political capital of the Empire from 1571 to 1578. The numerous palaces and the grand entrances with intricate art work have been recognized as a world heritage site by UNESCO. Akbar also began construction of his own tomb at Sikandra near Agra in 1600 CE.

Prince Salim (b. 1569 son of Hindu Rajput princess from Amber), who would later be known as Emperor Jahangir showed signs of restlessness at the end of a long reign by his father Akbar. During the absence of his father from Agra he pronounced himself as the king and turned rebellious. Akbar was able to wrestle the throne back. Salim did not have to worry about his sibling’s aspirations to the throne. His two brothers, Murad and Daniyal, had both died early from alcoholism.

Jahangir began his era as a Mughal emperor after the death of Akbar in the year 1605. He considered his third son Prince Khurram (future Shah Jahan-born 1592 of Hindu Rajput princess Manmati), his favourite. Rana of Mewar and Prince Khurram had a standoff that resulted in a treaty acceptable to both parties. Khurram was kept busy with several campaigns in Bengal and Kashmir. Jahangir claimed the victories of Khurram – Shah Jahan as his own.

Prince Khurram, who would later be known as Emperor Shah Jahan, ascended to the throne after a tumultuous succession battle. With the wealth created by Akbar, the Mughal kingdom was probably the richest in the world. Prince Khurram gave himself the title of Shah Jahan, the ‘King of the World’ and this was the name that was immortalized by history. With his imagination and aspiration, Shah Jahan gained a reputation as an aesthete par excellence. He built the black marble pavilion at the Shalimar Gardens in Srinagar and a white marble palace in Ajmer. He also built a tomb for his father, Jahangir in Lahore and built a massive city Shahajanabad in Delhi but his imagination surpassed all Mughal glory in his most famous building the Taj Mahal. It was in Shahajanabad that his daughter Jahanara built the marketplace called Chandni Chowk.

His beloved wife Arjuman Banu (daughter of Asaf Khan and niece of Nur Jahan) died while delivering their fourteenth child in the year 1631. The distraught emperor started building a memorial for her the following year. The Taj Mahal, named for Arjuman Banu, who was called Mumtaz Mahal, became one of the Seven Wonders of the World.

The great Jama Masjid built by him was the largest in India at the time. He renamed Delhi after himself as Shahjahanabad. The Red Fort made of red sandstone built during his reign near Jama Masjid around the same time came to be regarded as the seat of power of India itself. The Prime Minister of India addresses the nation from the ramparts of this fort on Independence day even to this age.Shah Jahan also built or renovated forts in Delhi and in Agra. White marble chambers that served as living quarters and other halls for public audiences are examples of classic Mughal architecture. Here in Agra fort, Shah Jahan would spend eight of his last years as a prisoner of his son, Aurangzeb shuffling between the hallways of the palace, squinting at the distant silhouette of his famous Taj Mahal on the banks of River Jamuna..

In 1679, Aurangzeb enforced the jizyah tax on Non-Muslims like Zakāt tax was enforced on Muslims. This action by the emperor, incited rebellion among Hindus and others in many parts of the empire notably the Jats, Sikhs, and Rajputs forces in the north and Maratha forces in the Deccan. The emperor managed to crush the rebellions in the north. Aurangzeb was compelled to move his headquarters to Aurangabad in the Deccan to mount a costly campaign against Maratha guerrilla fighters led by Shivaji and his successors, which lasted twenty-six years until he died in 1707 at the age of eighty-nine.

The imperial family directly descended from two of the worlds greatest conquerors: Genghis Khan, founder of the largest contiguous empire in the history of the world; and the Amir, Taimurlong or Tamerlane the Great. The direct ancestors of the Mughal emperors, at one point or another, directly ruled all areas from Eastern Europe to the Sea of Japan, and from the Middle East to Russian Plains. They also ruled some of the most powerful states of the medieval world such as Turkey, Persia, India and China. Their ancestors were further also credited with stabilizing the social, cultural and economic aspects of life between, Europe and Asia and opening the extensive trade route known as the Silk Road that connected various parts of the continent. Due to descent from Genghis Khan, the family was called Mughal, or mogul, persianized version of the former's clan name Mongol.The English word mogul (e.g. media mogul, business mogul) was coined by this dynasty, meaning influential or powerful, or a tycoon. From their descent from Tamerlane, also called the Amir, the family used the title of Mirza, shortened Amirzade, literally meaning 'born of the Amir'.[2] The burial places of the Emperors illustrate their expanding empire, as the first Emperor Babur, born in Uzbekistan is buried in Afghanistan, his sons and grandsons, namely Akbar the Great and Jahangir in India and Pakistan respectively and later descendants, Shah Jahan and Aurangzeb in Hindustan. The last Emperor, Bahadur Shah Zafar is buried in Burma.

They were also a prominent influence of literature in Urdu, Hindi, and Bengali. They have been continuously portrayed in many films, the most famous of which, multi-million dollar Mughal-e-Azam about Emperor Jahangir's love story; considered an Indian classic and epic film and also the Bollywood film Jodhaa Akbar about Emperor Akbar's (Emperor Jahangir's father) love story. Emperor Jahangir's son was the Prince Khurram who later went on to become Emperor Shah Jahan and built one of the seven Wonders of the World, the famous Taj Mahal to memorialize his love for his wife.

Mughal Empire

Main article: Mughal Empire

The Mughal Empire lasted for more than three centuries. The Mughal Empire was one of the largest centralized states in pre-modern history and was the precursor to the British Indian Empire.The titles of the first of the six Mughal Emperors receive varying degrees of prominence in present-day Pakistan and India. Some favour Babur the pioneer and others his great-grandson, Shah Jahan (r. 1628-58), builder of the Taj Mahal and other magnificent buildings. The other two prominent rulers were Akbar (r. 1556-1605) and Aurangzeb (r. 1658-1707). Both rulers expanded the empire greatly and were able administrators. However, Akbar was known for his religious tolerance and administrative genius, whereas Aurangzeb was a just ruler but a proselytizer of orthodox Islam across the heterodox Indian landscape.

Babur

Babur was the first Mughal emperor. He was born on 14 Feb 1483 in present day Uzbekistan, the eldest son of Amir Umar Shaykh Mirza, the son of Abū Saʿīd Mirza (and grandson of [Miran Shah], who was himself son of Timur) and his wife Qutlugh Nigar Khanum, daughter of Younus Khan, the ruler of Moghulistan (and great-great grandson of [abhavh Timur]], the son of Esen Buqa II, who was the great-great-great grandson of Chaghatai Khan, the second born son of Genghis Khan). Babur was known for his love of beauty in addition to his military ability. Babur concentrated on gaining control of northwestern India.He was invited to India by Daulat Khan Lodi and Rana Sanga who wanted to end the Lodi dynasty. He defeated Ibrahim Lodi in 1526 at the First battle of Panipat, a town north of Delhi. In 1527 he defeated Rana Sanga, rajput rulers and allies at khanua. Babur then turned to the tasks of persuading his Central Asian followers to stay on in India and of overcoming other contenders for power, mainly the Rajputs and the Afghans. He succeeded in both tasks but died shortly thereafter on 25 December 1530 in Agra. He was later buried in Kabul.Babur kept the record of his life in Chagatay Turkish, the spoken language of the Timurids and the whole Turco-Mongol world at the time. Baburnama is one of the longest examples of sustained narrative prose in Chagatai Turkish. Akbar's regent, Bairam Khan, a Turcoman of eastern Anatolian and Azerbaijani origin whose father and grandfather had joined Babur's service. Bayram Khan wrote poetry in Chaghatai and Persian. His son, Abdul-Rahim Khankhanan, was fluent in Chaghatai, Hindi, and Persian and composed in all three languages. Using Babur's own text he translated the Baburnama into Persian. The Chaghatai original was last seen in the imperial library sometime between 1628 and 1638 during Jahangir's reign.

Humayun

Babur’s favorite son Humayun took the reins of the empire after his father succumbed to disease at the young age of forty-seven.In 1539, Humayun and Sher Khan met in battle in Chausa, between Varanasi and Patna. Humayun barely escaped with his own life and in the next year, in 1540, his army of 40,000 lost to the Afghan army of 15,000 of Sher Khan. A popular Pashtun Afghan General "Khulas Khan Marwat" was leading Sher Shah Suri's Army. This was the first Military Adventure of Khulas Khan Marwat and he became soon, a nightmare for Mughals.

Sher Khan's Army under the command of Khulas Khan Marwat had now become the monarch in Delhi under the name Sher Shah Suri and ruled from 1540 to 1545. Sher Shah Suri consolidated his kingdom from Punjab to Bengal (the first to enter Bengal after Ala-ud-din Khilji, more than two centuries earlier). He was credited with having organized and administered the government and military in such a way that future Mughal kings used it as their own models. He also added to the fort in Delhi (supposed site of Indraprastha), first started by Humayun, and now called the Purana Qila (Old Fort). The Masjid Qila-i-Kuhna inside the fort is a masterpiece of the period, though only parts of it have survived.

The charred remains of Sher Shah were taken to a tomb at Sasaram (in present day Bihar), midway between Varanasi and Gaya. Although rarely visited, the future great Mughal builders like Akbar, Jahangir and Shah Jahan emulated the architecture of this tomb. The massive palace-like mausoleum is three stories and fifty meters high., Sher Shah’s son Islam Shah held on to power until 1553 and following his death the Sur dynasty lost most of its clout due to strife and famine.

Humayun was a keen astronomer, and in fact he died due to a fall from the rooftop of Sher Shah’s Delhi palace in 1556. Thus Humayun ruled in India barely for ten years and died at the age of forty-eight, leaving behind Akbar then only thirteen-year-old as his heir. As a tribute to his father, Akbar later built the Humayun’s tomb in Delhi (completed in 1571), from red sandstone, that would become the precursor of future Mughal architecture. Akbar’s mother and Humayun’s wife Hamida Banu Begum personally supervised the building of the tomb in his birth place.

Akbar

Akbar succeeded his father, Humayun whose rule was interrupted by the Afghan Sur Dynasty, which rebelled against him. It was only just before his death that Humayun was able to regain the empire and leave it to his son. In restoring and expanding Mughal rule, Akbar based his authority on the ability and loyalty of his followers, irrespective of their religion. In 1564 the jizya tax on non-Muslims was abolished, and bans on temple building and Hindu pilgrimages were lifted.Akbar's methods of administration reinforced his power against two possible sources of challenge—the Afghan-Turkish aristocracy and the traditional interpreters of Islamic law, the ulama. He created a ranked imperial service based on ability rather than birth, whose members were obliged to serve wherever required. They were remunerated with cash rather than land and were kept away from their inherited estates, thus centralizing the imperial power base and assuring its supremacy. The military and political functions of the imperial service were separate from those of revenue collection, which was supervised by the imperial treasury. This system of administration, known as the mansabdari, was based on loyal service and cash payments and was the backbone of the Mughal Empire; its effectiveness depended on personal loyalty to the emperor and his ability and willingness to choose, remunerate, and supervise.

Akbar declared himself the final arbiter in all disputes of law derived from the Qur'an and the sharia. He backed his religious authority primarily with his authority in the state. In 1580 he also initiated a syncretic court religion called the Din-i-Ilahi (Divine Faith). In theory, the new faith was compatible with any other, provided that the devotee was loyal to the emperor. In practice, however, its ritual and content profoundly offended orthodox Muslims. The ulema found their influence undermined.

Several well known heritage sites were built during the reign of Akbar. The fort city of Fatehpur Sikri was used as the political capital of the Empire from 1571 to 1578. The numerous palaces and the grand entrances with intricate art work have been recognized as a world heritage site by UNESCO. Akbar also began construction of his own tomb at Sikandra near Agra in 1600 CE.

Jahangir

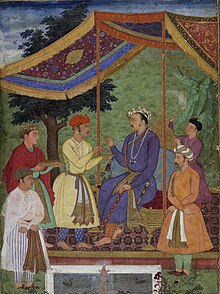

Mughal Emperor Jahangir receiving his two sons, in 1605-06.

Jahangir began his era as a Mughal emperor after the death of Akbar in the year 1605. He considered his third son Prince Khurram (future Shah Jahan-born 1592 of Hindu Rajput princess Manmati), his favourite. Rana of Mewar and Prince Khurram had a standoff that resulted in a treaty acceptable to both parties. Khurram was kept busy with several campaigns in Bengal and Kashmir. Jahangir claimed the victories of Khurram – Shah Jahan as his own.

Shah Jahan

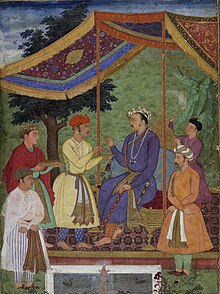

Shah Jahan on a Terrace Holding a Pendant Set with His Portrait.jpg

His beloved wife Arjuman Banu (daughter of Asaf Khan and niece of Nur Jahan) died while delivering their fourteenth child in the year 1631. The distraught emperor started building a memorial for her the following year. The Taj Mahal, named for Arjuman Banu, who was called Mumtaz Mahal, became one of the Seven Wonders of the World.

The great Jama Masjid built by him was the largest in India at the time. He renamed Delhi after himself as Shahjahanabad. The Red Fort made of red sandstone built during his reign near Jama Masjid around the same time came to be regarded as the seat of power of India itself. The Prime Minister of India addresses the nation from the ramparts of this fort on Independence day even to this age.Shah Jahan also built or renovated forts in Delhi and in Agra. White marble chambers that served as living quarters and other halls for public audiences are examples of classic Mughal architecture. Here in Agra fort, Shah Jahan would spend eight of his last years as a prisoner of his son, Aurangzeb shuffling between the hallways of the palace, squinting at the distant silhouette of his famous Taj Mahal on the banks of River Jamuna..

Aurangzeb

Aurangzeb, who was given the title "Alamgir" or "world-seizer," by his father, is known for expanding the empire's frontiers and for his acceptance of Islam law. During his reign, the Mughal empire reached its greatest extent (the Bijapur and Golconda Sultanates which had been reduced to vassalage by Shah Jahan were formally annexed).In 1679, Aurangzeb enforced the jizyah tax on Non-Muslims like Zakāt tax was enforced on Muslims. This action by the emperor, incited rebellion among Hindus and others in many parts of the empire notably the Jats, Sikhs, and Rajputs forces in the north and Maratha forces in the Deccan. The emperor managed to crush the rebellions in the north. Aurangzeb was compelled to move his headquarters to Aurangabad in the Deccan to mount a costly campaign against Maratha guerrilla fighters led by Shivaji and his successors, which lasted twenty-six years until he died in 1707 at the age of eighty-nine.